A very frequent problem in dentistry are the alterations in growth and development, especially malocclusion and particularly mesiocclusion, which is one of the occlusopathies that must receive an early treatment due to the functional and morphological disorders that they cause in addition to the magnitude that they may reach. This paper is based on the clinical case of a patient treated in the Pediatric Stomatology Clinic of the Faculty of Stomatology of the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosi. It is a pediatric patient, a four-year old boy, who manifests crossed bite. We proceeded recording all diagnostic elements and chose as treatment plan Functional Orthopedics through the use of Ponce’s Functional Orthopedic Device (PFOD). The results were very satisfactory from the very start when the device was set in place. This was due to the fact that the change of therapeutic position (CTC) was completely accomplished setting the bite back to normal, owing to the age of the patient and his anatomic and physiological characteristics. Three days after revision, the incisive relationship was corrected, we will continue using the PFOD in order to change the muscular memory, consolidate the results, and reach greater advantages. Conclusions: The mere fact of correcting the incisive relationship of patients with deciduous dentition, will allow a completely different growth and development through physiological means favoring orofacial functions and a morphological conformation within normal boundaries that will benefit function, aesthetics and health.

Key words: Mesiocclusion, Ponce’s Device, Deciduous dentition, Early diagnosis, Change of Therapeutic Position

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR:

Yuritzi Silahua, División Académica de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco.

Av. Valle del Golfo Mza. 22 Lote 8 Dept. 13 Fracc. Valle Real, Pomoca, Nacajuca Tabasco, Mèxico. CP: 86220. Telephone: 52 (993) 2695754. Cellphoe: 52 (993) 1441596.

Email: [email protected]

Occlusion refers to the relationships that are established when the dental arches come in contact, whether this contact is centered, protruding or with lateral movements, as well as their relationships with the surrounding soft or hard tissues. The development of an occlusion or a malocclusion is the result of the interactions between genetically determined factors and extrinsic environmental factors, which include the orofacial functions that behave in a constant manner during specific periods (1, 2).

It has been argued that individuals learn to behave instinctively, and that these behaviors that become fixed due to this learning process are known as habits. A habit can be defined as an acquired custom or practice due to the frequent repetition of a same act that in the beginning is done consciously and later unconsciously. These are considered physiological or functional, there are also non-physiological habits like the sucking of the thumb, pacifiers or the lip, oral breathing, lingual interposition at rest, and infant swallowing that may provoke malocclusion or dental-skeletal malformations, all of which could alter the normal development of the stomagtognathic system, a bone deformation that is going to have a greater or lesser repercussion according to the age that the habit begins, the younger the age, the greater the damage and the longer the genetic factors persist or are added, the greater the malformations that occur in the child (1, 2, 3).

Health professionals such as pediatric stomatologists must identify the alterations of growth and development, in this case malocclusions, and treat them properly, whether they are of genetic origin or associated with pernicious habits (4).

Epigenetics: This new field of research has concurred with the growing comprehension of the human genome, which at the same time has enabled the functional correlations of genes with the environmental agents involved with the beginning and progression of diseases (5).

The crossed bite described above may represent a real mesiocclusion with genetic background or as well, may represent a crossed bite that was the consequence of certain habit, mainly the non-physiological behavior of the tongue.

The act of swallowing is a biological and coordinated function, formed by a neurological connection, a synergic and antagonistic mechanism of muscular actions ruled by reflex arcs, no lingual protrusion and frontward position is produced (3, 2).

Atypical swallowing is caused by an imbalance between the circumoral muscles and the tongue due to tonsillitis, neuromuscular imbalance, macroglossia, ankyloglossia, early loss of deciduous teeth in the frontal region, breathing through the mouth, thumb sucking, frontal open bite, disharmony between the bony bases. It is characterized by the interposition of the tongue between the dental arches during the act of swallowing, this is known as protractile tongue. In order to swallow, the individual needs to create a void that in conjunction with the movements of the tongue impels the food towards the pharynx (4, 2).

Types of atypical swallowing.

According to Baume, there are four types of terminal planes in primary dentition, taking as reference the distal faces of the second primary molars, these are:

The diagnosis should be based not only on clinical observations and anamnesis, it must be done through an adequate clinical history, which constitutes the principal element of a diagnosis. A detailed clinical examination is necessary along with the data obtained from panoramic, lateral cephalic and periapical radiographs in the study models and any other additional study required for each particular case. Additionally, the growth pattern must be evaluated in order to decide what type of device will be used (1,6).

The purpose of the functional treatment is the neuromuscular conduction by reflex of the action of the device, given by the origin of the therapeutic forces coming from the musculature, these reflex muscular reactions are sagittal, transverse and vertical and determinedly activate the total function of the matrix (6).

Ponce’s modified orthopedic devise was derived from a Bimler C, its purpose is to enhance the participation response of patients with deciduous dentition; it is indicated for patients with frontal crossed bite, or class III with genetic or epigenetic pronounced mesial terminal plane, or exclusively with inversed incisive relationship without yet presenting alteration in the molar relation. It is ideal for children between three and a half years, to six years old, where patient participation is doubtful and there is a possibility of not using, breaking or losing the device. It is not counter-indicated with mixed dentition, but patients that have reached that condition are old enough to collaborate with the use of a Bimler C.

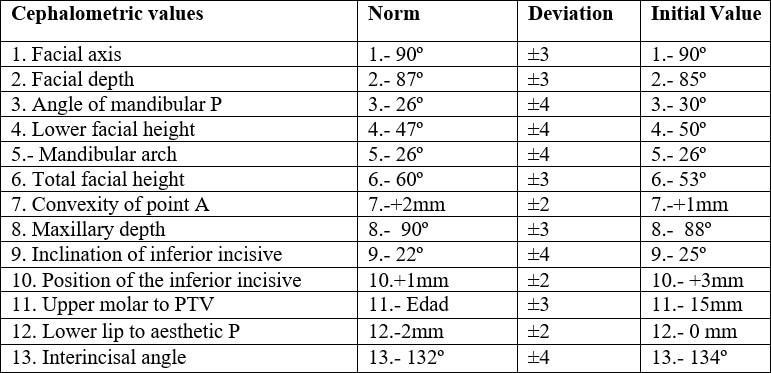

The patient is a boy four years and eleven months old, who presents frontal crossed bite. After clinical examination and occlusion analysis it is determined that he presents a terminal mesial slight to the right and pronounced to the left, middle line deviation to the right, canine relation I, negative incise relation and closed Type 2 Baume’s arch (Figure 2). Diagnosis elements were elaborated: the medical history, the study and work models, panoramic and lateral x-ray of the skull, exterior and interior oral photos. The medical history evealed the following habits: atypical swallowing, thumb sucking, bruxism, onychophagia. Ricketts cephalometric analysis revealed that factors were within normality (Figure 3, Table 1). The frontal photo allows us to observe unbalanced facial thirds and slight facial asymmetry with a more prominent left pinna. The profile photo reveals a prominent inferior facial third (Figure 4).

Mesiocclusion due to genetic and environmental factors, with midline by unilateral or vicious chewing. The cephalometric diagnosis reveals that at this stage there is no structural only dental affectation.

Following the initial session where the data related above were obtained we proceeded to obtain the working model with strips set on the second deciduous upper molars, securing the precision of the size, so that it could be retrieved with ease but snug enough in order to have an adequate control of its retrieval of the device by the patient’s mother. Once the imprint with alignate was obtained, the strips were retrieved with band-removing tweezers and set on the imprint making sure that the strips were placed on the right position, with the occlusal edge of the band facing the back of the alignate, the positive in plaster is obtained where the strips will be in the same place as in the patient. From this session to the next the patient is left with interproximal rubber bands in interproximal mesial of second deciduous molars so that there is no discomfort in the session of the device delivery.

The laboratory phase was initially carried out by soldering the seals to the strips and polishing this part, all of the wire elements are waxed, the CTC is done, in this case retro-translation with rotation to compensate for the deviation of the midline, and is acrylized. Later it is detailed, polished and washed leaving the device as shown in Figure 1.

Upon the second session the interproximal bands are retrieved and the device is set in place watching if the CPT created in the laboratory is reproduced, which in this case was very satisfactory (Figure 5). Indications of use and activation are given; it is important to stress that its use is constant, removing only for cleaning during the night, and to activate the screw once a week in accordance to the very particular response of each patient.

During the third session, three days after having set the PFOD, the incisor relationship was observed almost uncrossed in its entirety. This is a response that reveals the efficiency of the PFOD in the patient, and the response of the body in patients of early age (Figure 6).

The evidenced changes have been accomplished in multiple patients treated at the Pediatric Stomalogy Clinic with the use of the PFOD resolving this occlusopathy. The clinic case presented in this work is yet another evidence of the satisfactory results obtained in a short time due to the early-age related anatomic-physiologic characteristics and the efficiency of the PFOD. The main reasons why this alteration is not treated at an early stage is because of the parents lack of knowledge of the existence of these type of devices that can guarantee positive results, which is a cosequence of the dearth of public awarenes disclosure in the area of dentistry.

It is important to treat this occlusopathogenesis early, since to allow these cases to evolve and to reach the growth peaks in these conditions can lead to epigenetic alterations becoming structural and the genetic ones have severe consequences that imply treatments with very complex devices and even arrive to the need of surgical means. Furthermore, throughout their childhood and sometimes adolescence the patient will present important myofunctional alterations that do not allow a normal life, from the correct exercise of orofacial functions, among them mastication, to psychological factors due to the aesthetic alterations that affect the patient disturbing their social development.

The importance of an early treatment is essential when dealing with malocclusion, particularly in some instances like mesiocclusion or crossed frontal bite, whether it is genetically related or not. The benefits are enormous and more easily attainable, restoring not just the stomatognathic system health but of overall wellbeing of the patient. In this context disclosing early treatment should be a priority.

The research presented in this paper was possible thanks to the generous assistance of the Universidad Juarez Autonoma de Tabasco and the Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi, who through their Summer of Scientific Research program, sponsored the first author’s mobility between both institutions.