Introduction.- Malocclusions are among the most frequent oral alterations, and according to the World Health Organization are ranked third place in terms of oral pathologies after caries and periodontal disease. An adequate evaluation of the need for orthodontic treatment can be considered of great interest for public health dental programs. The Dental Aesthetics Index (DAI) is an ideal instrument for detecting malocclusions and the need for treatment.

Objective.- To determine the prevalence of dental malocclusions and the need for treatment in 12 to 15 year old Mexican schoolchildren using the DAI.

Methods.- A descriptive, cross-sectional, prospective and correlation study was conducted in 187 schoolchildren between 12 and 15 years of age from a public secondary school in Monterrey city. The severity of the malocclusion, as well as the need for orthodontic treatment, were measured according to the 10 components of the DAI.

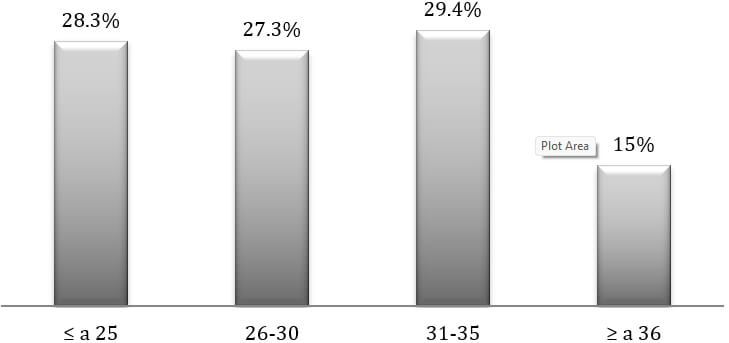

Results.- The maxillary and mandibular irregularities were the most prevalent with 82.4 and 88.2% respectively and the need for treatment according to the DAI was 29.4%, which indicates a severe malocclusion and its treatment should be convenient.

Discussion.- A mild malocclusion (≤ to 25) was found in 28.3%, which means that it requires a minor orthodontic treatment or no treatment. Regarding a moderate malocclusion (26-30) it obtained a 27.3%, this means that they only require a slight orthodontic treatment. Regarding severe malocclusion (31-35) a high percentage was obtained, which requires a highly desirable treatment.

Conclusion.- It was determined that dental malocclusions were high, with predominance in maxillary and mandibular irregularities, which indicates that half of the population requires a highly desirable and priority orthodontic treatment. Immediate orthodontic care is therefore suggested, before the last peak of growth to improve occlusal conditions and restore oral health.

Key words: Malocclusion, Epidemiology in orthodontics, Treatment.

Introducción.- Según la Organización Mundial de la Salud, las maloclusiones ocupan el tercer lugar en patologías bucales después de la caries y la enfermedad periodontal. Una evaluación adecuada de la necesidad de un tratamiento de ortodoncia puede considerarse de gran interés para los programas dentales de salud pública. El Índice de Estética Dental (DAI) es un instrumento ideal para detectar maloclusiones y su necesidad de tratamiento.

Objetivo.- Determinar la prevalencia de maloclusiones dentales y la necesidad de tratamiento en escolares mexicanos de 12 a 15 años utilizando el DAI.

Métodos.- Se realizó un estudio descriptivo, transversal, prospectivo y de correlación en 187 escolares entre 12 y 15 años de una escuela secundaria de Monterrey. La severidad de la maloclusión, así como la necesidad de tratamiento de ortodoncia, se midieron de acuerdo con los 10 componentes del DAI.

Resultados.- Las irregularidades maxilar y mandibular fueron las más prevalentes con 82,4 y 88,2% respectivamente y la necesidad de tratamiento según el DAI fue de 29,4%, lo que indica una maloclusión severa y su tratamiento debe ser conveniente.

Discusión.- Se encontró una maloclusión leve (≤ a 25) en el 28,3%, lo que significa que requiere un tratamiento de ortodoncia menor o ningún tratamiento. Respecto a una maloclusión moderada (26-30) obtuvo un 27,3%, esto significa que solo requieren un ligero tratamiento de ortodoncia. En cuanto a la maloclusión severa (31-35) se obtuvo un alto porcentaje, lo que requiere un tratamiento altamente deseable.

Conclusión.- Se determinó que las maloclusiones dentales fueron elevadas, con predominio de las irregularidades maxilares y mandibulares, lo que indica que la mitad de la población requiere un tratamiento de ortodoncia altamente deseable y prioritario. Por lo tanto, se sugiere un cuidado de ortodoncia inmediato, antes del último pico de crecimiento, para mejorar las condiciones oclusales y restaurar la salud bucal.

Palabras clave: Maloclusión, Epidemiología en Ortodoncia, Tratamiento.

Malocclusions are among the most frequent oral alterations, and according to the World Health Organization it is ranked third in terms of oral pathologies after caries and periodontal disease1. Malocclusions are defined as an abnormal alignment of the inclinations of the teeth once the jaws are in occlusion, these can be caused by various situations such as genetics, functionality and traumatism that come to affect the soft and hard tissues of the oral cavity2-3.

An adequate evaluation of the need for orthodontic treatment can be considered of great interest for public health dental programs. Several studies have investigated the severity of malocclusions according to age, specific populations and diverse ethnic groups. However, there are few studies in Mexico on the issues of the orthodontic treatment need in children4-5. The Dental Aesthetics Index has been adopted by the WHO since 1997 and is considered an ideal instrument for epidemiological studies in the detection of malocclusions and the need for treatment. It consists of a list of features or occlusal conditions in ordered categories and a scale of degrees that allows measuring the severity of malocclusions, this condition makes it reproducible and guides us according to the needs with respect to the orthodontic treatment of the population6-7. Several epidemiological studies have evaluated the distribution and severity of malocclusions. Garbin et al. in a Brazilian population like Cueto et al. in Chile, have reported the prevalence of malocclusions in a range of 63 to 66% using the same instrument8-9. The prevalence study reported in India by Sureshbabu et al. varies from 20 to 43%10. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of dental malocclusions and their correlation with the need for treatment in 12 to 15 year-old Mexican schoolchildren using the DAI.

A descriptive, cross-sectional, prospective and correlation study was conducted in 187 schoolchildren of both sexes between 12 and 15 years of age from a public secondary school in the municipality of Monterrey, during the January-December 2019 period. Sample size was calculated using the Epi Info ™ Version 7.2 program. The sample was selected by probabilistic sampling. The inclusion criteria were the authorization of the parents through an informed consent, children with no congenital malformations, children who have not undergone orthodontic treatment at any previous stage and the age range of this study group; the exclusion were the children/adolescent's refusal to the oral examination and the elimination of those who had an orthodontic treatment; and the elimination criteria Descriptive statistical procedures and Pearson correlation were used through the program SPSS Inc; Version 21. The present study was accepted and approved by the Ethics Committee of the career of Dentist Surgeon of the University of Monterrey. The oral examination was performed by General Dentists, an Orthodontist and Healthists using periodontal probe, millimetric rule, tongue ablaze and natural light. The severity of malocclusion as well as the need for orthodontic treatment were measured according to the 10 components of the DAI (Dental Aesthetic Index):

The final result of the DAI is given by a regression equation using the following formula: Lost teeth (x 6) + Crowding + Spacing + Diastema (x 3) + Maxillary irregularity + Mandibular irregularity + Maxillary overjet (x 2) + Mandibular overjet ( x 4) + Open bite (x 4) + Molar ratio (x 3) + 13.

The respective cut points of the DAI are divided as the following:

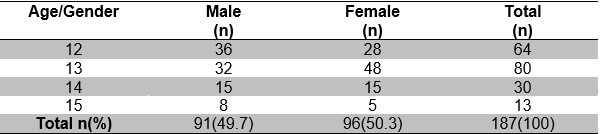

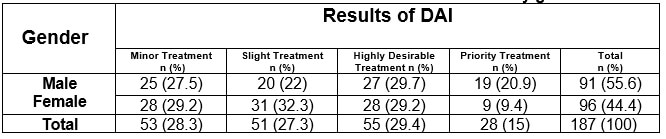

Out of the 187 students that were evaluated, 50.3% were female and 49.7 were male, the average age was 12.95 ± .9 years and regarding the school grade, 44.5% were in the 2nd grade, 41.4% in 1st. grade and 12% in 3rd. grade. The distribution by gender of the study population is found in table 1.

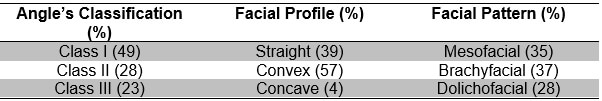

Regarding the Angle’s classification, 49% had a class I molar, 28% a class II and 23% class III, the facial profile of schoolchildren maintained a 58% convex, 38% proved to be straight and only a 4% was concave, the facial pattern was distributed in 37% for brachyfacial, 35% obtained a mesofacial pattern and 28% dolichofacial. The distribution of the malocclusion type, facial profile and facial pattern can be found in table 2.

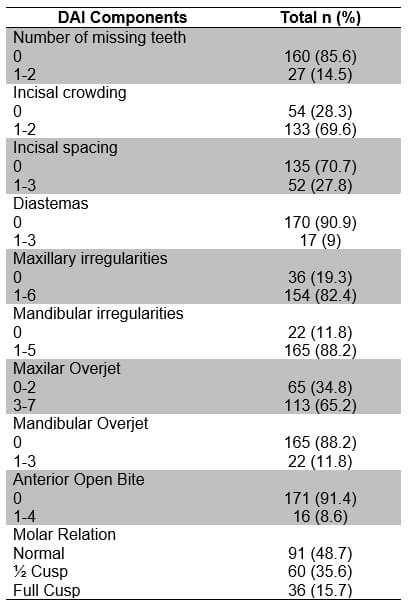

The distributions of the components of the Dental Esthetics Index can be seen in the table 3.

Regarding the need for treatment according to the cut-off points of the DAI, 28.3% had a stable occlusion with a score of ≤ to 25, where the treatment need is minor or does not need orthodontic treatment, 27.3% resulted with a score of between 26 and 30, which means the presence of a minor malocclusion and equivalent to perform a slight treatment, 29.4% took a score of 31 to 35, which indicates a severe malocclusion and orthodontic treatment should be highly desirable and finally in 15% detected a score of ≥ 36, which means a disabling malocclusion and orthodontic treatment is a priority. Graph 1 shows the need for orthodontic treatment according to the DAI.

Table 4 shows the distribution of the need for orthodontic treatment by gender, in which the female sex predominated in the minor treatment and slight treatment with 29.2% and 32.3% respectively, and the male sex predominated in the highly desirable treatment and priority treatment with 29.7% and 20.9% respectively.

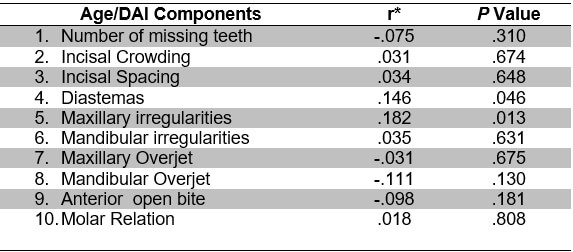

A Pearson correlation was performed to see the relationship between age and the DAI components, where low but statistically significant correlations were found in the components of diastemas and mandibular irregularities (P = .046 and .013) respectively (table 5).

The present study was conducted in order to detect the prevalence of malocclusions and their need for orthodontic treatment in a school population of 1st, 2nd and 3rd grade of secondary school, this through a multicultural instrument recommended by the World Health Organization which integrates psychosocial elements and physical features of malocclusion and mainly measures occlusal disharmony and values unacceptable aesthetics. The results will be discussed in each of the components of the DAI, the prevalence of malocclusions, the need for orthodontic treatment as well as the findings on the correlation between age and these components.

The results obtained regarding the missing teeth category, gave 14.5% of the study population that had one or more missing teeth, either in the maxilla or mandible, which were similar to the Shivakumar et al.13 studies conducted in India with 11%, opposed to the study by Freitas et al.11 in Brazil, which obtained a prevalence of 7.8%, taking into account that its study was in a larger sample. Regarding the incisal crowding component, we obtained a 69.6% crowding in both maxilla and mandible, which was similar to the study by Garbin et al.8, Which obtained 66.6% and disagreed with the studies of Shivakumar et al.13 which obtained 37.2%. In the incisal spacing category this study presented 27.8% of spaces between 1 and 3mm maxillomandibular, similar to that of Shivakumar et al.13 and Freitas et al.11 with 26.5% and 21.3% respectively and different from the study by Garbin et al.8 who obtained 11.3%.

On the other hand, of the 187 students, only 9% presented diastemas in the middle line in a range of 1 to 3 mm, which is almost similar to the study by Garbin et al.8 with 8.7% but different from the one below the Shivakumar at al.13 and Freitas et al.11 studies with 18.3% and 14.4% respectively. In the subject of maxillary irregularities of the 100% of the sample, 82.4% had maxillary irregularities between 1 and 6 mm, well above the studies of Shivakumar et al.13 with 25.6%, Garbin et al.8 with 23.7% and Freitas et al.11 with 8.3%. Regarding, mandibular irregularities in our study were presented in a very high prevalence from 1 to 5 mm was presented with 88.2%, very different from the studies by Garbin et al.8, Shivakumar et al.13 and Freitas et al.11 with 35.1%., 19.3% and 3.8% respectively.

In relation to maxillary overjet, a high percentage of this component in 65.2%, in comparison with the studies of Garbin et al.8, Freitas et al.11 and Shivakumar et al.13, which obtained percentages of 37.8%, 17.5% and 6.9% respectively. This could be due to the different geographic locations and the population by gender difference. The results about mandibular overjet showed only 11.8% of the population that obtained a negative or inverse overjet of 1 to 3 mm, unlike the study published by Garbin et al.8, Shivakumar et al.13 and Freitas et al.11, which obtained low percentages of between .2 and 1.09%.

In the component of anterior open bite, only 8.6% of open bite of 1 to 4mm was obtained, a greater result than the published works in Brazil8 and India11, which obtained ranges between 2.1 and 3.4%.

The results about molar relation yielded 48.7%, as was the study by Freitas et al.11 with 47%, but unlike the studies by Garbin et al.8 and Shivakumar et al.13 with 70.5% and 91.6% respectively. In this study, of the 187 students, only 35.6% presented a molar relation of ½ cusp, either mesially or distally, in contrast to the work of Garbin et al.8, which obtained 7.7% and Shivakumar et al.13, with 4.5%. On the topic of complete cusp molar relation, the results of this study showed percentages almost identical to those of Brazil8 with a range of 15 to 21.6% and different from the study of India11, which obtained 3.9% in this component.

In relation to the prevalence of class I, II and III malocclusions, out of the 100% of the students of the present study, 49% presented class I malocclusion, very similar to the study by Talley et al.15 with 52.8% and different from the studies by Garbin et al.8 and Mafla et al.14 who obtained the highest results with 37.3% and 68.7% equitably. Regarding class II malocclusion, our study showed 28%, this result very similar to the studies of Mafla et al.14, Garbin et al.8, Talley et al.15 which obtained 17.6%, 28.6% and 33.9% respectively. Regarding class III malocclusions, the present study obtained a high percentage of 23% in comparison with the studies of Mafla et al.14, Garbin et al.,8 Talley et al.15, which were among a range from .8 to 13.7%.

The need for orthodontic treatment as well as the severity of malocclusion are the most important characteristics of the Dental Aesthetic Index. In the current study, the results corresponding to a mild malocclusion (≤ to 25) were 28.3%, which means that it requires a minor orthodontic treatment or no treatment even, a result similar to the study by Mafla et al.14, Alemán et al.17 and Almeida et al.18 who obtained a range of 32 to 34.4%.Regarding a moderate malocclusion (26-30) it obtained a 27.3%, this means that they only require a slight orthodontic treatment, these results were similar to those of Cueto et al.9 with 27.9%, German et al.17 with 24.4% and Almeida et al.18 with 32.8%. Regarding severe malocclusion (31-35) a high percentage was obtained with 29.4, which requires a highly desirable treatment compared to the studies of Shivakumar et al.13, Kunal Jha et al.12 and Garbin et al.8 which had results of 3.7%, 9.5% and 10.9% respectively and similar to the study by Mafla et al.14 with 20.4%. Finally, the prevalence of invalidating malocclusions (≥ 36) in this study was 15%, a result similar to the studies by Pérez et al.16, Almeida et al.18 and Cueto et al.9 who obtained 13.7%, 15.1% and 15.7% equitably and contrasting with the studies of Shivakumar et al.13 with .5% and Kunal Jha et al.12 with a 3.3 %.

In this study, a correlation was made between the variables of age and the various components of the ICD, the study showed low but significant correlations in the variables diastemas and mandibular irregularities of .146 and .182 with a significance of .046 and .013 respectively, of the reference and discussion studies that were obtained, none of them showed correlations between these variables, so this part cannot be discussed with other authors.

The prevalence of dental malocclusions in junior high school students was high, with predominance of maxillary and mandibular irregularities, which indicates that half of the population requires a highly desirable and priority orthodontic treatment.

There was no association with malocclusions and gender, but correlation with age was found, which suggests immediate orthodontic care, before the last peak of school growth to improve occlusal conditions and return oral health impacting on biological well-being, psychological and social.